Investigating the Response of Acropora cervicornis to Ocean Acidification

The following project was my first foray into academic research during my undergraduate years at the University of Miami. This research experience taught me that science is a commitment to explore and understand through hard work and creativity. From the long-term maintenance of corals in mesocosms to the team-first attitude required to conduct all the biological assays, the work was methodical and planned. This experience fostered a love for the process of science I carry to this day. I maintain this project summary as a reminder of where my research career began.

The ocean uptakes nearly a quarter of the emitted carbon dioxide. This increased uptake of CO2 is a phenomenon known as ocean acidification (OA) and results in the lowering of seawater pH and a reduction in the aragonite saturation state. Due to the reef's metabolism, the change in reef carbonate chemistry naturally changes throughout the day, and this diel cycle may be exacerbated by OA. Since OA alters the carbonate chemistry, it therefore reduces the calcification rate of corals, which precipitate an aragonite skeleton. The reduction in growth rates threaten the construction of coral reefs and their important ecological functions and ecosystem services. Previous studies investigating the effect of OA on Acropora cervicornis support the idea that OA depresses skeletal density but does not impair total linear extension. As part of a large team of undergraduate and graduate students under the direction of Dr. Chris Langdon, I further investigated the effect of OA on calcification rate and coral physiology including, holobiont respiration, symbiont photosynthesis, symbiont density, chlorophyll-a content of the symbiont cells, and lipid density.

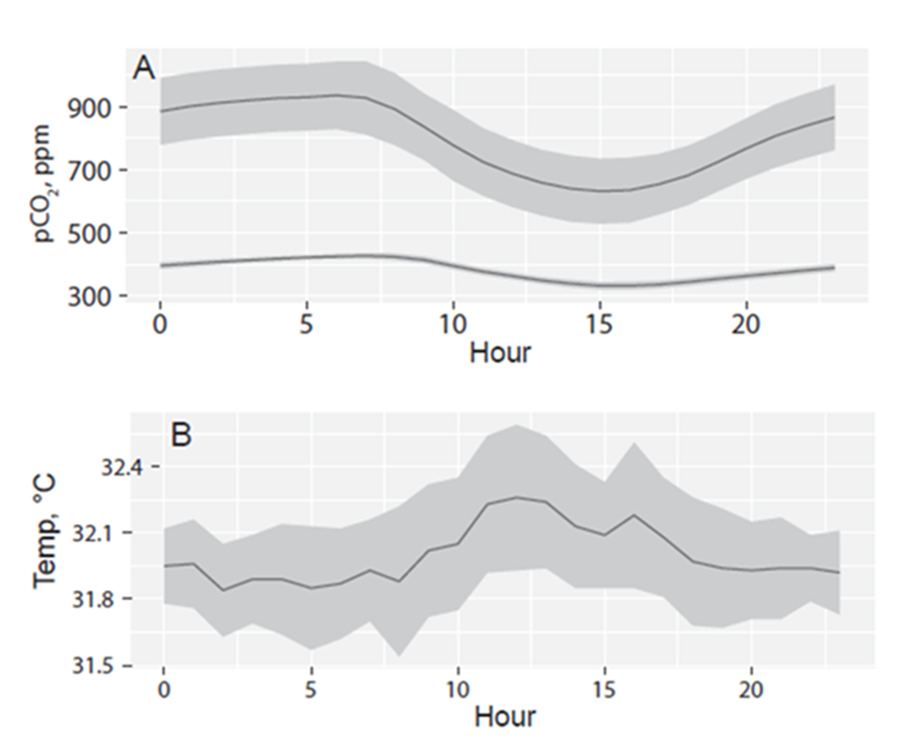

In the lab, A. cervicornis was placed under normal and high pCO2 stress to understand how the coral holobiont is affected by heightened pCO2 at different sub-bleaching temperatures. Corals were divided into 4 temperature groups: 26 °C, 27 °C, 28° C, and 29 °C. These temperatures are all below the mean bleaching threshold (31 °C) of A. cervicornis. Corals were further divided into two pCO2 groups: 400ppm, current levels derived from NOAA sensors at Cheeca Rocks in Islamorada, Florida, and 1000ppm, projected levels by the end of the century. The tanks bubbled with the low pCO2, 400ppm, had an average pH of 8.0 and tanks bubbled with projected levels of high pCO2, 1000ppm, had an average pH of 7.7. Forty corals were grown at each temperature at ambient conditions for three months to establish healthy fragments and then randomly divided into low and high pCO2 tanks. Then for the next four months, the corals were maintained and weekly measurements of physiology were measured. At the conclusion of the experiment, corals were blasted with a waterpik using filtered seawater to extract all tissue and lipids from the fragments. The coral tissue-symbiont homogenate was filtered and extracted onto filter paper for individual analysis of lipids, chlorophyll-a, and symbiont count. Remaining coral skeletons were dried and then dipped in paraffin wax to determine the surface area of the fragment to normalize all biological parameters in analysis.

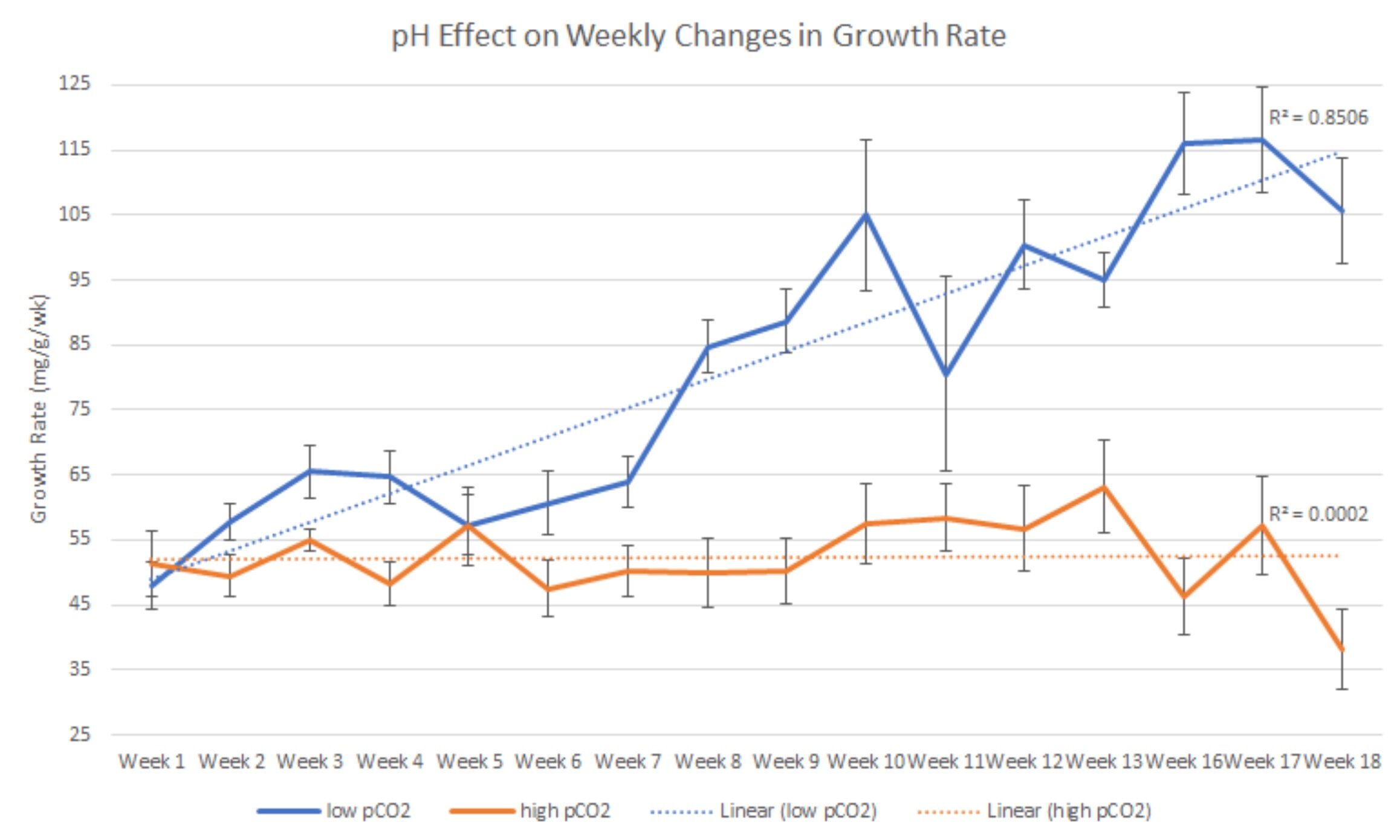

For my part of the study, I first investigated the changes in calcification rate of the 27° C tanks. Calcification was measured weekly using the buoyant weight technique, and the amount of growth from placement into treatment tanks was used to calculate each corals calcification rate. Calcification rate of corals exposed to high pCO2 were nearly constant throughout the 20 weeks studied while calcification rate of corals exposed to low pCO2 was linear throughout the study. This suggests that coral growth rates will be dampened by the end of the century when the ocean has a mean pCO2 of 1000ppm.

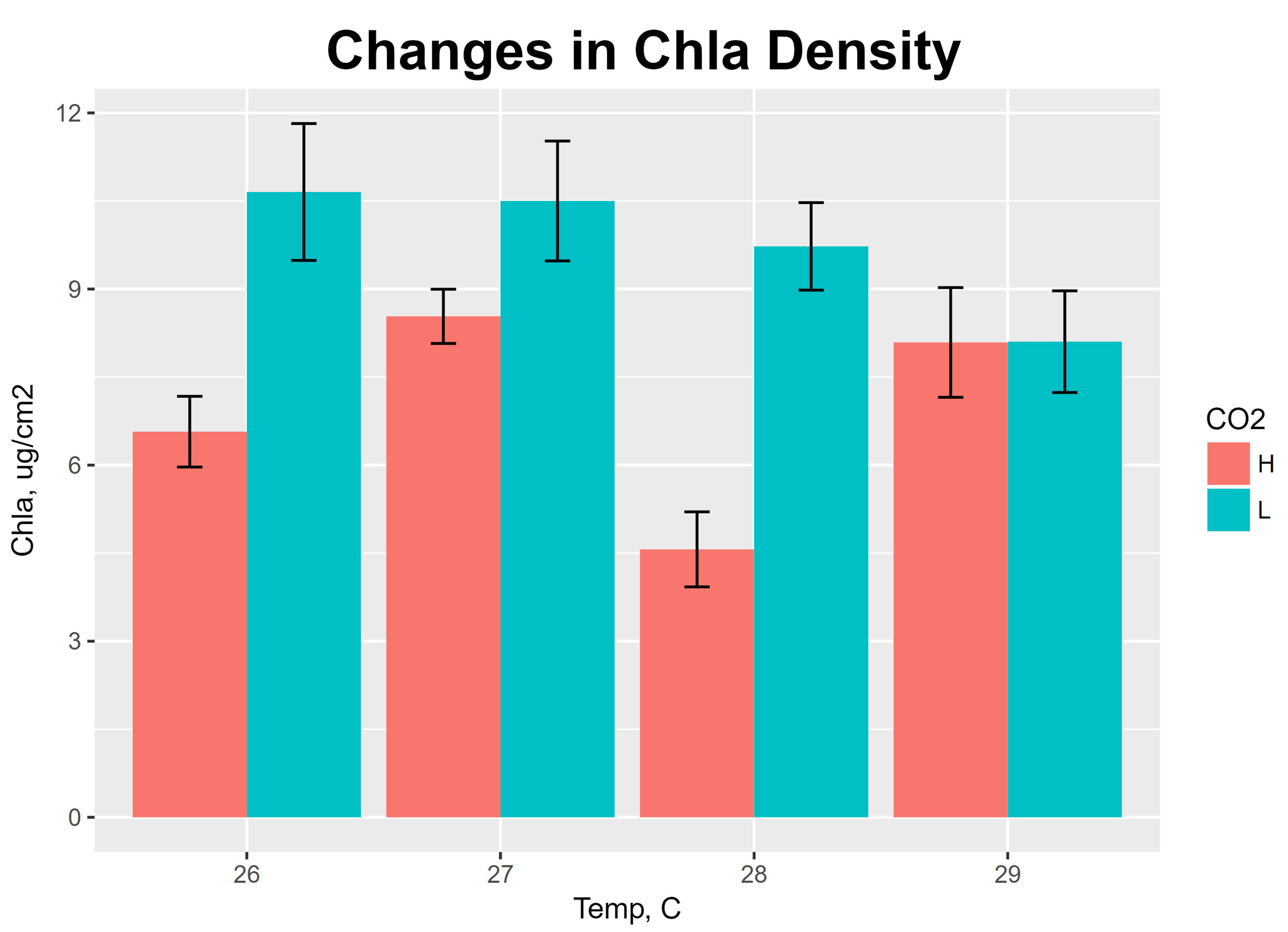

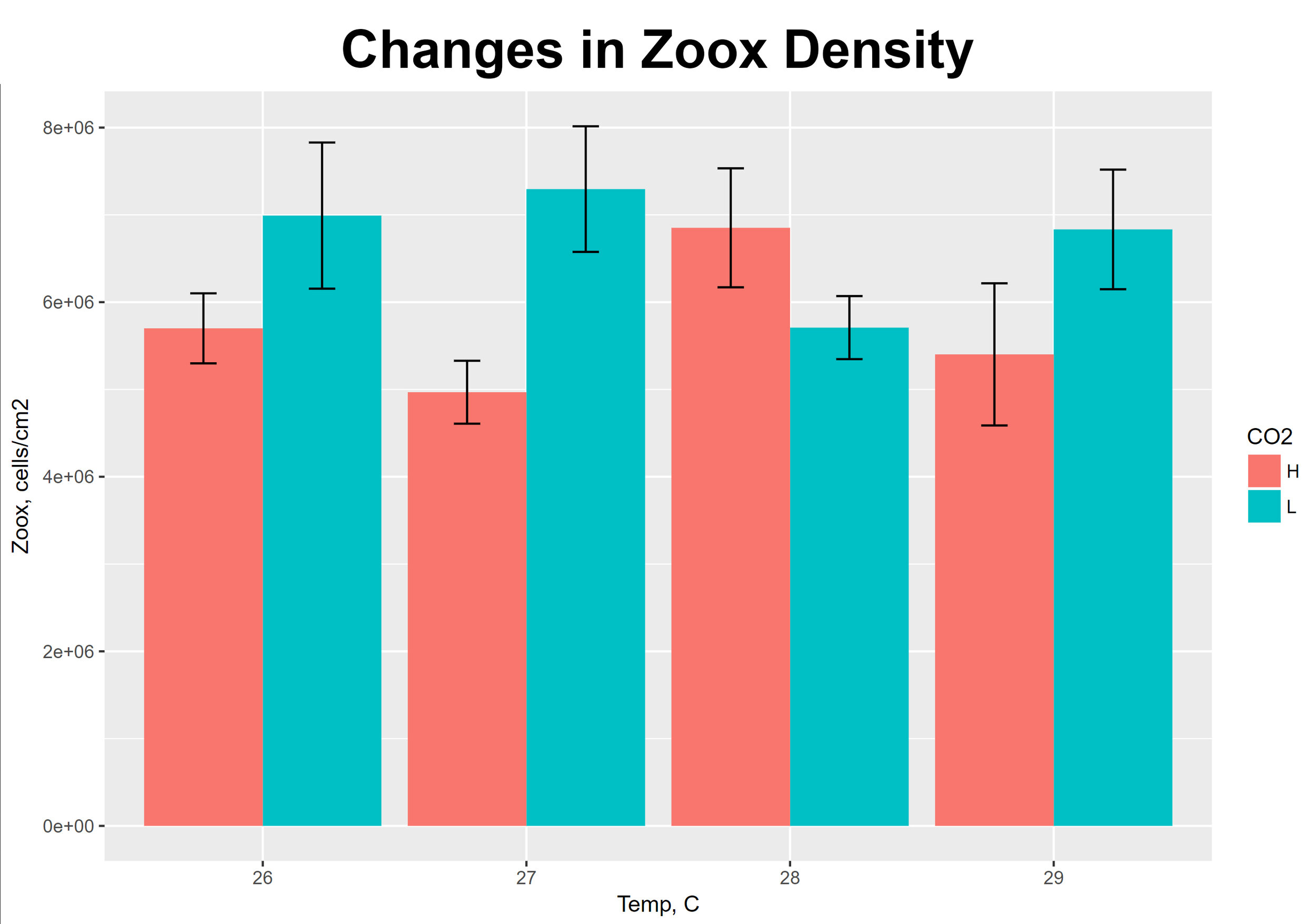

I then investigated the changes in symbiont cell density and chlorophyll-a content. For most temperature pairings, there was a higher symbiont density in the lower pCO2 tank. Similarly, for most temperature pairings, there was a higher concentration of chlorophyll-a, the dominant chlorophyll form in zooxanthallae, in corals maintened in lower pCO2 tanks. These decreases in total symbionts and reduction of chlorphyll-a density in high pCO2 environments have significant implications for coral respiration as corals receive most of their energy from their photosynthetic symbionts. Further, it is possible that bleaching of corals, expelling of symbionts by the coral host, may lead to increased rates of mortality in corals exposed to high pCO2 as the corals may already be energy deficient.

In conjunction with other studies investigating the effect of OA on corals, this work underscored the effect of OA on changing biological parameters of coral health in addition to the reduction in calcification rates. OA, therefore, threatens to change reef framework and may depress the financial, nutritional, and recreational benefits of coral reefs.

Working in Dr. Langdon’s lab was my first experience with coral reef ecology research. The lessons I learned and skills I gained in this lab prepared myself for independent research where I could answer questions of my own.